By Mike Randle

The populations of U.S. regions look quite different than they did 60 years ago. In 1955, the American West was home to just 24 million people. Today, it has grown dramatically to 74.1 million residents. The growth of the Midwest and Northeast since 1955 has been minimal compared to the South and West. The Midwest currently has 62.5 million (43 million in 1955) and the Northeast has 61.3 million (42 million in 1955) residents respectively. In contrast, the population of the American South has ballooned from 48 million to over 121 million people in 60 years, a total that is very close to matching the populations of the Northeast and the Midwest combined. If Census migration patterns continue as they are, sometime in 2016 or 2017, the South will contain more people than the Northeast AND the Midwest combined.

If you Google “the South,” the first site that pops up is a Wikipedia page. Part of the copy on the page reads, “Apart from its climate, the living experience in the South increasingly resembles the rest of the nation. The arrival of millions of Northerners (especially in major metropolitan areas and coastal areas) and millions of Hispanics means the introduction of cultural values and social norms not rooted in Southern traditions. Observers conclude that collective identity and Southern distinctiveness are thus declining, particularly when defined against ‘an earlier South that was somehow more authentic, real, more unified and distinct.’ The process has worked both ways, however, with aspects of Southern culture spreading throughout a greater portion of the rest of the United States in a process termed ‘Southernization.’ ”

Today, the South is defined as a diverse economic engine that drives the nation’s economy. Go ahead and pick your economic indicator, whatever it might be. Use population, the number of metros in the U.S., retail purchases, manufacturing jobs, service jobs — whatever — the South always accounts for between 37 and 40 percent of the nation’s total or more.

In fact, the South leads all U.S. regions in every economic category the federal government tracks, including GDP. While the South doesn’t quite account for 40 percent of U.S. GDP, the region’s Gross Regional Product at $5.84 trillion in fiscal year 2014 dwarfs the West’s $4.05 trillion, which is in second place.

As for job creation, you can throw out that 40 percent figure most years. For example, from April 2012 to April 2013, the South accounted for 44 percent of all new jobs created in the U.S. Some years it’s over 50 percent of all new jobs created in the country.

There are no other U.S. regions that can remotely match the number of major market economies located in the American South. Of the 50 largest markets in the U.S., the South is home to 22, and the West is home to just 12. In the Northeast there are eight, the same number as in the Midwest.

Even more, look at post-recession population growth in the 50 largest U.S. metros. From 2010 to 2012, the eight largest markets in the Northeast saw their populations grow by a mere .78 percent. At .73 percent, growth was even more anemic in the eight largest markets in the Midwest.

But in the West, in the 12 markets there that are included in the 50 largest markets in the U.S., populations grew by 2.89 percent. Topping regional growth were the 22 Southern MSAs. They grew by 3.15 percent from 2010 to 2012. Clearly, the West and the South are dominating regional growth, and it has been that way for more than four decades.

The South’s economic bulls are its major markets, not necessarily its mega-markets such as Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Tampa Bay and Miami. Those mega-markets are huge drivers, but what makes the South a mile wide and a mile deep are the secondary major markets such as Austin, San Antonio, New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Nashville, Memphis, Charlotte, Raleigh-Durham, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Orlando, Greenville, Birmingham, Hampton Roads, Louisville. . .you can go on and on when naming growing economic centers of influence in the South that are not the size of a Chicago, New York, Houston or Atlanta.

And that list doesn’t even reach to the South’s dynamic mid-markets. The American South has dozens of metro players driving the world’s fourth largest economy. And that’s what makes the South’s economy what it is today. It is a team sport, where other regions are home to single, massive metro economies — like Chicago, New York or Boston — with few supporting team members. To prove that point, name another metro economic powerhouse in Illinois, New York or Massachusetts.

The “other” South

Almost exactly 10 years ago, in the fall of 2004, SB&D published a cover story optimistically titled, “After five tough years, deals are back in the rural South and manufacturing is leading the way.” The cover photo featured former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee with Hino Motors executives breaking ground on the new Japanese automotive supplier’s plant in the Delta region of Arkansas. Those “five tough years” mentioned in the title were tough because during that time so many rural Southern plants closed, picked up their equipment and offshored to Asia and elsewhere.

Many have forgotten, but when George W. Bush assumed the office of President in the winter of 2001, things weren’t so rosy with the South’s or the nation’s economy. There was a two- or three-year stretch from 2004 to 2006 when it seemed that the economy was stable. . .but it really wasn’t. Offshoring, while slowing, continued. And virtually all of North America had lost a sizable chunk of its manufacturing base and was bleeding critical jobs at alarming rates to Asia, specifically China.

If the nation was losing its manufacturing base to offshoring, what was happening in the rural South, where manufacturing rules? Repeating a popular phrase in today’s media, parts of the rural South’s economy were a “dumpster fire.” There was a herd mentality at the time to offshore manufacturing capacity — an economic phenomenon that began in the early 1990s and continued unabated for almost 15 more years — and the rural South was especially hard hit.

One of the reasons why the rural South’s manufacturing base was losing ground to offshoring from the early 1990s to around 2005 is that back then, much of the industry was “footloose.” Footlose industries are those that are not tied to a specific location or country, such as furniture, textiles and apparel manufacturing. Since that time, much of the manufacturing now done in the rural South is tied to a specific location. Automotive suppliers are a perfect example, as they need to be located near one of the Southern Auto Corridor’s 19 assembly plants. And the term “footloose” really needs a new definition because so many manufacturers are now making the decision to onshore, reshore, make it where you sell it, whatever you want to call it, in today’s economic model.

But conditions would get worse before they got better in small town South — offshoring slowed at about the same time the economy began to crater in 2007. Unemployment rates skyrocketed in many nonmetro areas during the Great Recession. Plant closures and mass layoff events occurred in much greater numbers than even at the height of the offshoring period. Instead of offshoring, many of the rural South’s manufacturing plants were simply shuttered during the recession.

Fast forward to 2015 and the U.S. economy is now hitting on all cylinders for the first time since the late 1990s. While the numbers aren’t in yet, as of this writing, 2014 should be the best job generating year since 1999. With 2.65 million people added to payrolls from January to November, 2014 will certainly be a banner year for job creation. Nonfarm payrolls grew by 321,000 in November. That figure represented the strongest job generating month in three years. It was preceded by payroll gains of 243,000 in October and 271,000 in September.

So, five years out of the worst recession post World War II, and some are comparing the current economy to the go-go 1990s. I recall former Nashville Chamber of Commerce President Fred Harris telling me in the late 1990s about the state of Nashville’s economy. “Michael, it is better than I have ever seen it. We have people who are working who don’t even want to work.” Fred’s statement was correct since Nashville’s unemployment rate was below three percent when he called me. Nashville is hot again, being called the “it” city, but it hasn’t reached full employment yet. (Nashville’s current unemployment rate is 5.3 percent.)

When major markets run out of labor, as Nashville did in the late 1990s, that is typically a good sign for the rural South. What occurs simply is this: job generation ramps up in the South’s metros to a point where labor availability is exhausted. That forces growing companies to look outside of metropolitan areas to find labor sheds that are available. In short, for a growing company to build to capacity in a white-hot economy, companies must locate in rural areas. . .the last frontier of labor availability.

Today, as the economy continues to grow, have rural regions benefited yet from tight labor markets in metropolitan areas? In September, Bill Bishop wrote in the Daily Yonder that 57 percent of rural residents in the U.S. lived in a county where the local employment rate either matched or was lower than the national average. That sounds like a pretty healthy number until you dig a little further into the data.

Bishop’s data indicated that almost all of those rural counties with unemployment rates lower than the national average are in the Great Plains, from Texas to North Dakota and Montana. The West and the Southeast, two of the fastest growing areas of the country, have fewer rural counties with unemployment rates that are below the national average.

Bishop wrote in the Daily Yonder article, “What was that about the Sunbelt? You remember the Sunbelt, right, the ever-growing, job-producing, always-booming heart of the nation’s economy? To find rural counties with unemployment rates at or below the national average, you have to swing your gaze to the Great Plains, or gasp, the Northeast. Don’t look at the Pacific Coast or the Southeast. Yep, the Great Plains just might be the new Sunbelt — only without the hype.”

Note to Bishop: Much of the rural South has lagged behind other U.S. region’s rural areas since Reconstruction. Furthermore, there’s a big difference between the Great Plains and the South. For one, rural counties in the South are more densely populated — although still rural — than those in the Great Plains. More densely populated rural counties in the South rely heavily on manufacturing jobs and those counties are the ones that “took the largest hits,” in the Great Recession according to an article written by Wyatt Orme for High Country News in September titled, “Rural and small town employment still lags.” The more sparsely populated rural counties, such as those in the Great Plains, rely mostly on agriculture as an economic base, which fared well during the recession. And oil and gas extraction is predominantly located in rural counties in the Great Plains, while little of that activity is seen in the rural Southeast.

The Economic Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture produced a study recently which showed that since the economic downturn began in 2007, both nonmetro and metro areas have made up losses in employment. However, employment has grown on average by only 1.57 percent cumulatively in nonmetro counties compared to 3.82 percent average growth in metro counties. From the second quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2014, metro employment grew by 5 percent, while nonmetro employment grew by just 1.1 percent, according to USDA.

In May of 2014, five years after the end of the recession, nonfarm employment in the U.S. reached pre-recession highs. Metro employment has surpassed pre-recession highs, but in the rural U.S., there are still about 800,000 fewer jobs than there were in 2007. About 500,000 of those lost jobs are in the American South.

Poverty rates in the nonmetro South remain higher than any other place in America. The latest data from the USDA and the Census Bureau show that 22.1 percent of rural Southerners are at or below the poverty level. That is a much greater percentage than any other U.S region when comparing metro and non-metro poverty.

Chart No. 1

Poverty rates by region and metro/non-metro residence, 2013

| Region | % Non-metro | % Metro |

| Northeast | 14.2 | 13.5 |

| Midwest | 13.6 | 13.3 |

| West | 16.2 | 14.9 |

| South | 22.1 | 15.2 |

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service using data from U.S. Census Bureau, 2014.

One aspect of the rural South’s economy that is not helping the situation is the fact that it is not growing. For the first time ever, population growth in rural counties in the U.S. is essentially nonexistent according to numbers gathered from the USDA in 2012 and 2013. According to Orme’s article, “Small towns and rural areas have seen periods of exodus in the past, but never before has rural America experienced population loss.”

Here is more data about population loss in rural counties from the USDA website: “The number of people living in nonmetropolitan (nonmetro) counties stood at 46.2 million in 2013 — nearly 15 percent of U.S. residents spread across 72 percent of the nation’s land area. Nonmetro areas lost population between July 2012 and 2013, continuing a three-year trend. While hundreds of individual counties have lost population over the years, this is the first period of overall population decline in nonmetro America.”

Further data from USDA showed that over 1,200 nonmetro counties in the U.S. have lost population since 2010 with a decline of 400,000 residents. Just over 700 nonmetro counties gained population, adding over 300,000 residents, for a net loss of just 100,000 people nationwide. It’s not much, but as written earlier, it is unprecedented simply because it has never occurred before.

This event is most certainly the result of the loss of jobs, particularly manufacturing jobs, during the recession. Mass layoffs over the past 20 years due to small town South manufacturers offshoring — coupled with the closing of factories during the recession — has created a flight to metros for people looking for work. According to a USDA report, zero population growth and even population losses in rural counties account for roughly half of nonmetro job growth deficits.

Chart No. 2

Rural vs. Urban. Unemployment Rates in Southern States 2013

| Rural | Urban | |

| Alabama | 7.6 | 6.1 |

| Arkansas | 8.6 | 6.9 |

| Florida | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| Georgia | 9.5 | 7.9 |

| Kentucky | 9.4 | 7.5 |

| Louisiana | 7.5 | 5.9 |

| Mississippi | 9.7 | 7.5 |

| Missouri | 6.7 | 6.5 |

| North Carolina | 9.4 | 7.7 |

| Oklahoma | 5.3 | 5.5 |

| South Carolina | 10.0 | 7.2 |

| Tennessee | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| Texas | 6.4 | 6.3 |

| Virginia | 7.7 | 5.3 |

| West Virginia | 7.3 | 6.0 |

Economic factors weighing in the rural South’s favor

The rural South has had many champions over the decades. Winthrop Rockefeller, Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton certainly stand out as powerful individuals who focused on improving the economic conditions of the rural South.

The rural South has had many champions over the decades. Winthrop Rockefeller, Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton certainly stand out as powerful individuals who focused on improving the economic conditions of the rural South.

On July 4, 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in a speech, “It is my conviction that the South presents right now the nation’s No. 1 economic problem — the nation’s problem — not merely the South’s. For we have an economic unbalance in the nation as a whole, due to this very condition of the South. It is an unbalance that can and must be righted, for the sake of the South and of the nation.”

Five years after the end of the Great Recession may not be enough time to evaluate the state of the rural South’s economy. But this we know; history has shown that there is no greater champion for the rural South than a fast-growing economy. The effects of the Great Recession created many skeptics when it comes to believing that the economy is really improving. But even the most ambivalent have to give a nod to this economy right now. Here are some facts:

* The U.S. economy has added jobs for 57 straight months, the longest sustained period in history.

* The U.S. has seen net job gains of 200,000 or more for 10 consecutive months, the longest stretch of 200,000-plus net monthly gains in over 16 years.

* In November there was a sharp rise in average hourly earnings.

* The unemployment rate in the U.S. has dropped from 8.3 percent in January 2012 to 5.8 percent in November 2014. The South’s’ unemployment rate in November was 6.2 percent.

* The manufacturing sector added 28,000 net new workers in November, the highest monthly total in 2014.

Last point is this — while job growth in rural areas in the U.S. has been less than half that of urban areas since the end of the recession, first quarter 2014 data showed a decent spike in rural job gains. It was the largest gain in net rural jobs since the end of the recession and it was maintained in the second quarter. Could this be the rural South’s time?

Last point is this — while job growth in rural areas in the U.S. has been less than half that of urban areas since the end of the recession, first quarter 2014 data showed a decent spike in rural job gains. It was the largest gain in net rural jobs since the end of the recession and it was maintained in the second quarter. Could this be the rural South’s time?

There are several economic factors working in the nonmetro South’s favor. For one, upcoming labor shortages in the region’s metros will naturally force growing companies to look to the rural South for labor. Economists are predicting real gross product to grow by 3.1 percent in 2015, a major improvement over the 2.2 percent expected for 2014. If that occurs, the South’s metropolitan areas will see much tighter labor markets by year’s end.

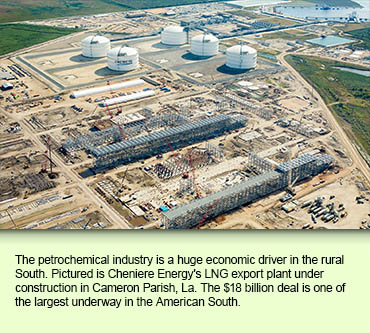

The very reason why the rural South took it on the chin may be the key factor behind recovering the jobs it lost in the recession. Manufacturing is growing in the South like no time in the past 25 years. There were more manufacturing announcements meeting or exceeding 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment in the 2014 SB&D 100 ranking than any year since 1992. And with reshoring not expected to peak for a few more years according to the Boston Consulting Group, we expect the manufacturing sector will continue to gain steam.

A spike in rural job generation is not the only economic development surprise in the South in 2014. Foreign direct investment from the Chinese is finally surfacing in the region. The Chinese have been a no-show in the U.S., essentially the last large Asian economy to make significant investments in the South, following the Japanese and the Koreans. In 2014, Chinese companies invested 20-fold more in the South in new plants and acquisitions than what they have done in any other year. And a good portion — about half — of those investments were made in nonmetro counties.

Chart No. 3

Rural vs. Urban: Population in Southern States 2013

| Rural 1980 | Rural 2013 | Urban 1980 | Urban 2013 | |

| Alabama | 1,100,514 | 1,159,361 | 2,793,511 | 3,674,361 |

| Arkansas | 1,095,600 | 1,152,099 | 1,190,757 | 2,959,373 |

| Florida | 447,307 | 702,636 | 7,674,145 | 18,850,224 |

| Georgia | 1,299,405 | 1,772,222 | 4,163,577 | 8,219,945 |

| Kentucky | 1,689,447 | 1,837,294 | 1,970,877 | 2,558,001 |

| Louisiana | 802,611 | 768,088 | 3,403,505 | 4,206,116 |

| Mississippi | 1,560,410 | 1,632,059 | 960,360 | 1,359,148 |

| Missouri | 1,342,220 | 1,556,587 | 3,574,546 | 4,487,584 |

| North Carolina | 1,688,108 | 2,208,984 | 4,191,987 | 7,639,076 |

| Oklahoma | 1,250,773 | 1,347,249 | 1,774,714 | 2,503,319 |

| South Carolina | 650,153 | 753,364 | 2,470,576 | 4,021,475 |

| Tennessee | 1,159,151 | 1,491,022 | 3,431,872 | 5,004,956 |

| Texas | 2,460,759 | 3,023,593 | 11,764,754 | 23,424,600 |

| Virginia | 999,497 | 1,061,716 | 4,335,161 | 7,198,689 |

| West Virginia | 819,286 | 714,605 | 1,130,900 | 1,139,699 |

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service

Education in the rural South is the key

If we are indeed in the midst of an economic run not seen in almost two decades, leaders in the rural South must understand that to maximize this rare opportunity, education is the key. The path politicos and educators are taking today to educate the rural South’s workforce is unique.

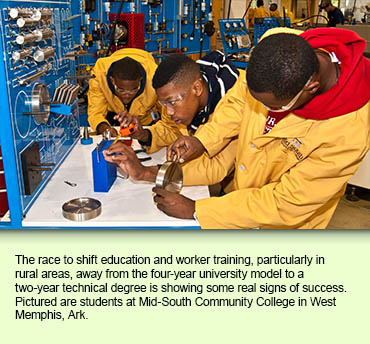

If a sustained, growing economy not seen since the late 1990s is underway, the rural South is engaging in a tactic that is critical to its recovery. The race to shift education and worker training, particularly in rural areas, away from the four-year university model to a two-year technical degree, is showing real signs of success.

Note the third item in Chart No. 4 (completing some college in the South) that has an asterisk. The percentage of people who have completed some college or earned a two-year degree in the rural and urban South is very close to being equal. This is the category the workforce states in the region are targeting in an effort to improve workforce skills. If those persons without a degree, but with some college, that are located in the rural South can complete at least their two-year degree — preferably in a trade — then the South’s nonmetros areas will be much more attractive to locating industry. Data shows this is now being accomplished better than at any time in years.

But there are barriers — like the history of the struggles of manufacturing up until 2007 when it began its resurgence — and stereotypes and other hurdles to clear in an effort to convince kids in the rural South that a two-year trade degree could land them a job paying six figures. For one, many of the parents and grandparents of those kids are the very ones who, working at a manufacturing plant, lost their jobs to offshoring and the recession.

Chart No. 4

Rural vs. Urban: Education in the South (Persons 25 and older)

| Not completing high school in the South | |||

| Rural 1980 | Urban 1980 | Rural 2013 | Urban 2013 |

| 45.3 | 41.6 | 21.4 | 14.2 |

| Completing high school only in the South | |||

| Rural 1980 | Urban 1980 | Rural 2013 | Urban 2013 |

| 26.0 | 31.4 | 37.1 | 29.4 |

| *Completing some college in the South | |||

| Rural 1980 | Urban 1980 | Rural 2013 | Urban 2013 |

| 9.4 | 12.52 | 27.6 | 29.3 |

| Completing college in the South | |||

| Rural 1980 | Urban 1980 | Rural 2013 | Urban 2013 |

| 9.1 | 13.6 | 15.0 | 27.0 |

*Includes two-year degrees. Source: USDA, Economic Research Service

Secondly, we have lost an entire generation of manufacturing workers in the region, particularly in the apparel, textile and furniture manufacturing sectors. Those industries are reshoring in healthy numbers, but for almost two decades, there were few if any significant new and expanded projects in those industries. That being the case, there was no need to train workers for those jobs.

Here is an example of what we lost and have regained in the course of more than 20 years. In 1996, the South saw, for the first time since World War II, the service sector beating out the manufacturing sector in total projects of 200 jobs or more and/or $30 million or more in captital investments. That year, there were 212 manufacturing projects and 361 service projects announced meeting or exceeding those thresholds in the South. It would get worse for manufacturing. The next year (1997) saw 407 big service deals and 229 manufacturing deals. In 2001, a recession year and the year China joined the WTO, there were 282 service and 164 manufacturing projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds of 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment. Those 164 deals represented the low performance point for manufacturing in our ranking since it was first published in 1993.

Move on to 2013 and everything has changed. In 2013, there were 410 manufacturing projects and 185 service projects announced in the South meeting or exceeding SB&D’s thresholds. The American South’s economy has done a backflip, from one that was consumer-oriented with service deals in some years tripling the number of manufacturing deals, to an economy that is firmly based in manufacturing. Make that an economy that is dominated by manufacturing when it comes to large, game-changing deals.

This change in the South’s economy caught educators and workforce training officials by surprise. After all, the revolution in the South’s economy to manufacturing-focalized has only been happening for five years, or since 2010. We saw clues of the aboutface as early as 2006, and then again in 2007, but the recession contracted that. Now that we are five years into it, educators know full well what the needs of industry are and they have made great strides in workforce training. One of those advances is dual enrollment, where a high school kid can receive training at a community college while attending high school.

Dr. Glen Fenter, president of Mid-South Community College in West Memphis, Ark., and a noted workforce educator in the Delta region of Arkansas, said this about the new model of accentuating two-year degrees over four-year degrees, particularly in nonmetro areas. “We are still, in this country, primarily educating folks with one goal in mind; they are all supposed to go off and get a four-year degree” Fenter said. “Unfortunately, the university system model was only designed to educate about 15 to 20 percent of our gene pool. The rest of those folks have no interest in being on that university campus, they are just being forced by our model to go there. And what happens? They go, they spend about $10,000 to $15,000 that first year, get deep in debt, jack up all of their financial aid, come back home, they can’t get any more financial aid and they have no chance of getting a job with anybody.”

Fenter continued about improvements in workforce training in the rural South, specifically new methods that are being implemented in the two-year degree model. “We have taken a big step, not just for the Southern region of the United States but for the entire country. I am convinced that our democracy is not sustainable unless we get back to a place in this country where we are producing goods and services that we can sell to the rest of the world. I think the South is uniquely positioned (because of improvements in workforce training) to see some unprecedented evolutions, but we are going to have to play smarter, be more aware of who our competitors are and understand what we have to do to win in this global economy.”

Conclusion

I have a special place in my heart for the rural South. After all, I have visited more than 1,850 nonmetro towns and counties in three decades, and in the fall quarter we barnstormed about 40 small towns in Kentucky. Over the years, dozens of those rural Southern towns and counties have transformed themselves into micropolitan and metro areas. Their success, their growth, means they aren’t defined as “rural” any longer by the Census Bureau. But don’t think that’s a knock on “rural.” Many companies prefer a rural location. Among other things, it makes them a big fish in a small pond. The rural South is also the least expensive place to manufacture in the most productive economy in the world.

Economic development, as it is practiced today, was invented by the mayor of tiny Columbia, Miss., way back in 1929. But the fact that the practice of economic development was concocted in a tiny town in a state that remains one of the poorest in the country, tells you something about the resiliency of the rural South when it comes to the desire to succeed.

The rural South’s economy as a whole has picked itself up and dusted itself off more times than any other place in America. It has recovered after being shaken time and again over the past 150 years. The rural South has come back from the depths of the Great Recession, from the age of offshoring, from the Great Depression to Reconstruction post Civil War. It’s economy is still not all the way back from the latest downturn. The rural South, once again, finds itself in a familiar situation. But the data we are seeing indicates that situation is about to change for the better. Again.